Your idea of human nature will inevitably shape the way that you think about politics. All ideologies seem to think that human nature is on their side, and, in their minds, this turns their political opinions into natural law while exposing the stupidity of their opponent’s ideas since they are clearly incompatible with nature itself.

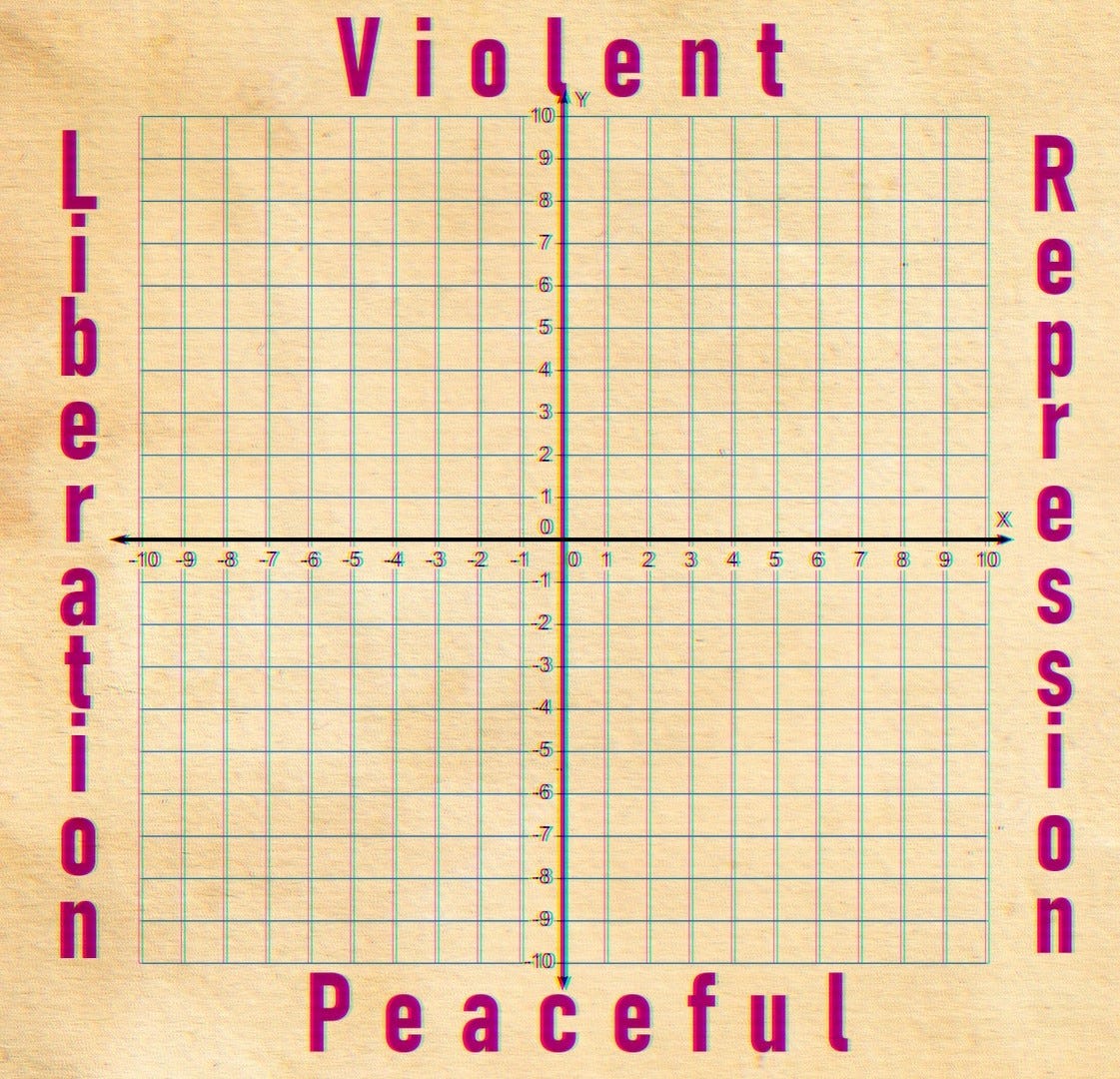

In this essay we will delineate the different conceptions about human nature that can be found across the political spectrum, to do this we will create a map; a political compass of human nature.

This essay will be a cooperation with Russell Walter, I highly encourage you to check his channel out, he is one of the best essayists out there:

Defining the map

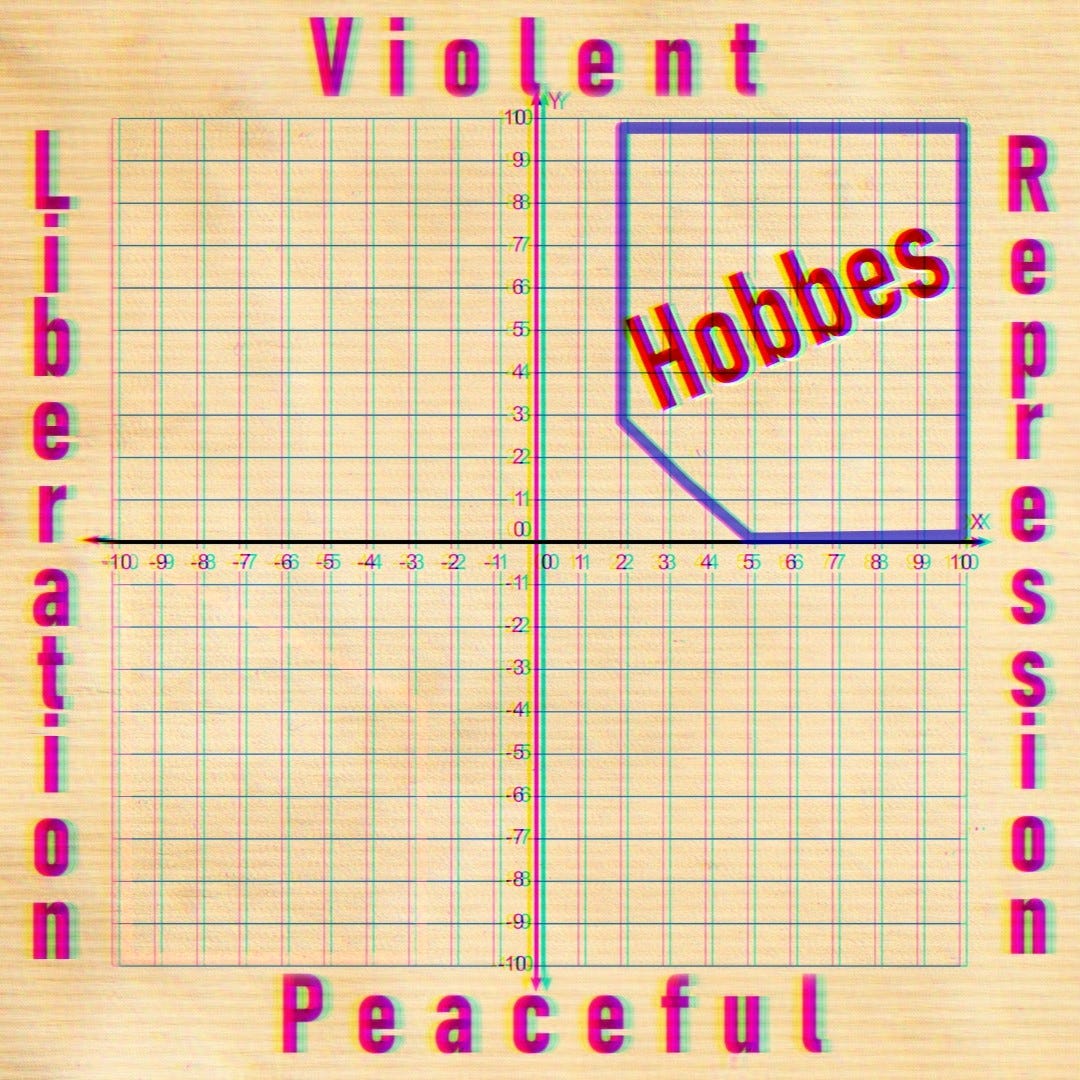

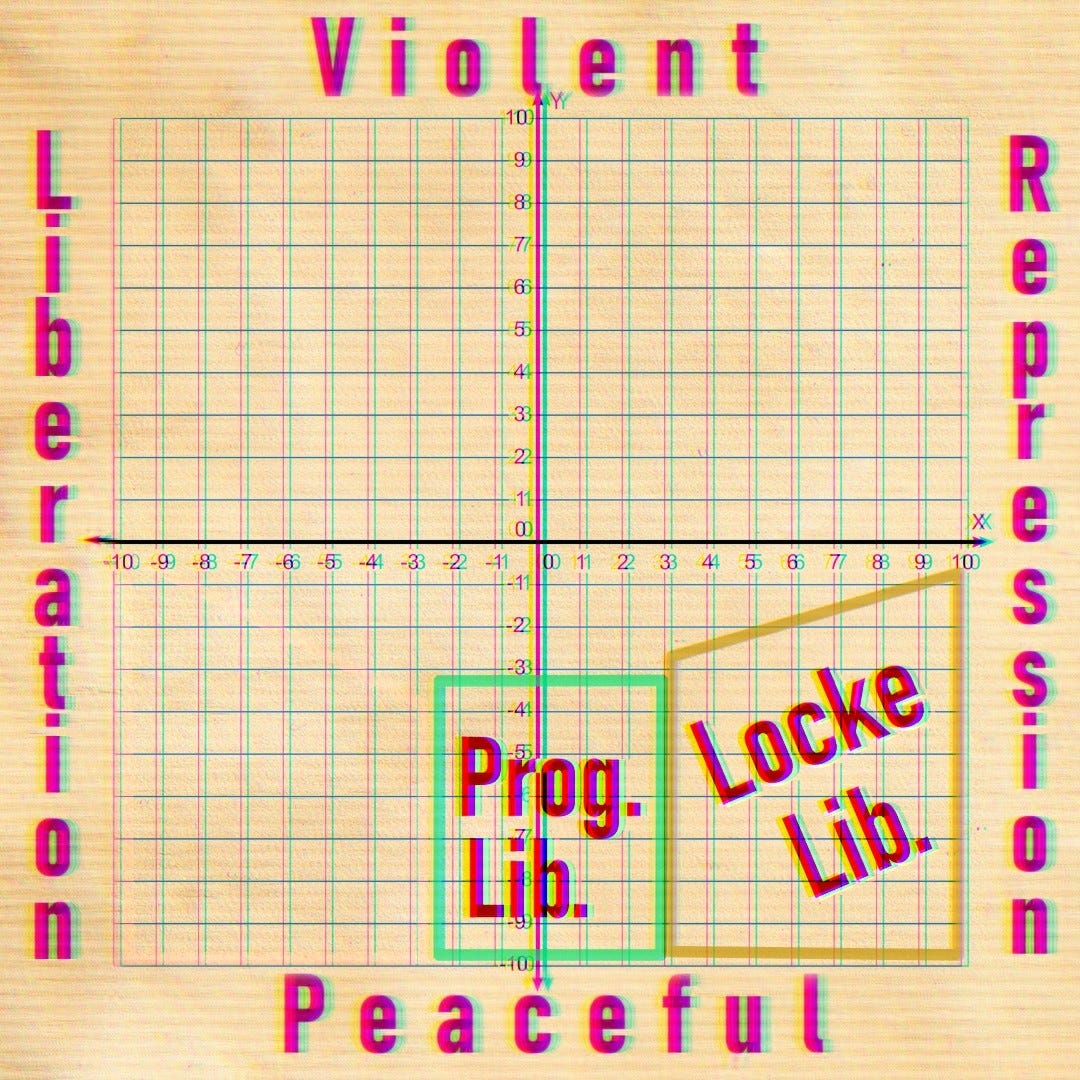

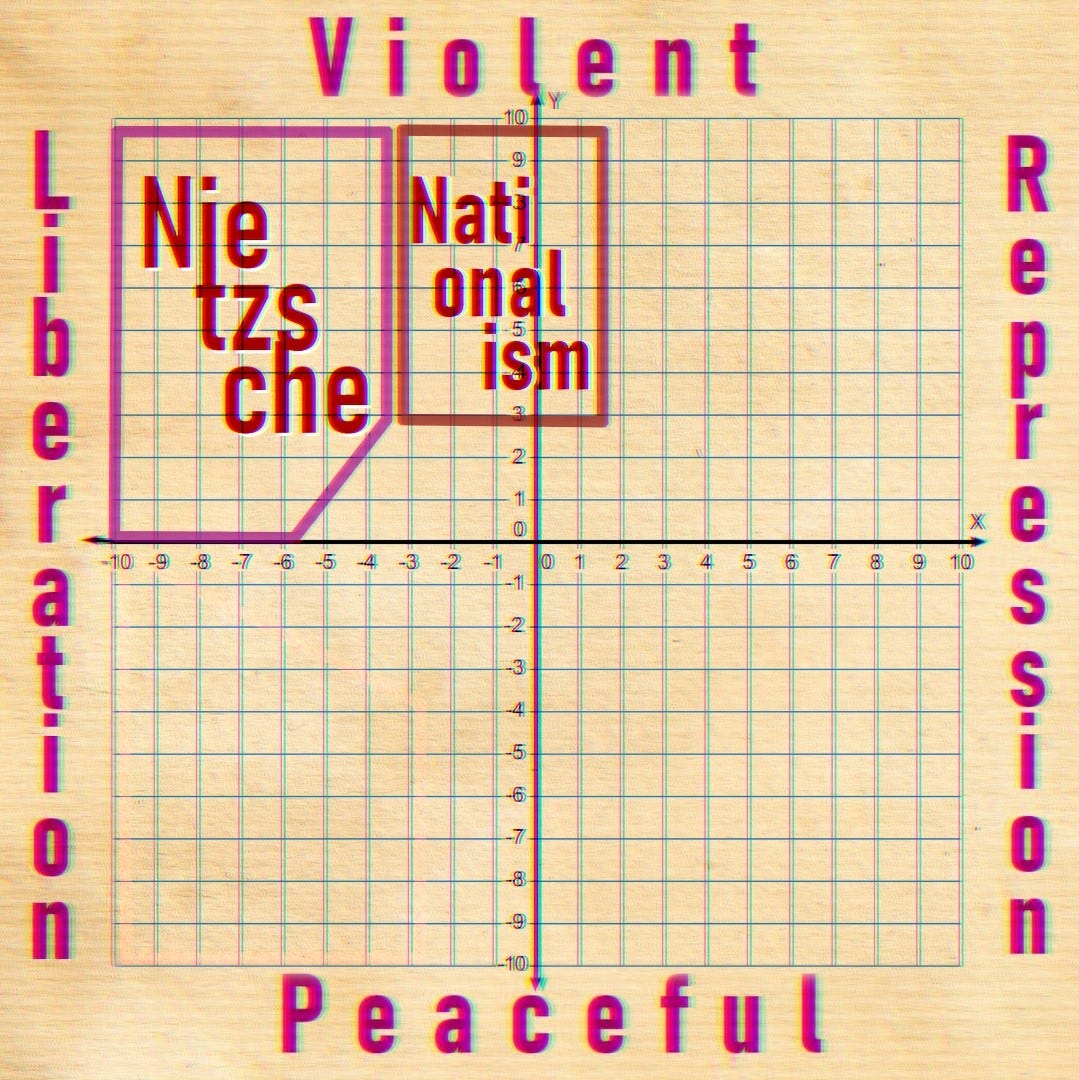

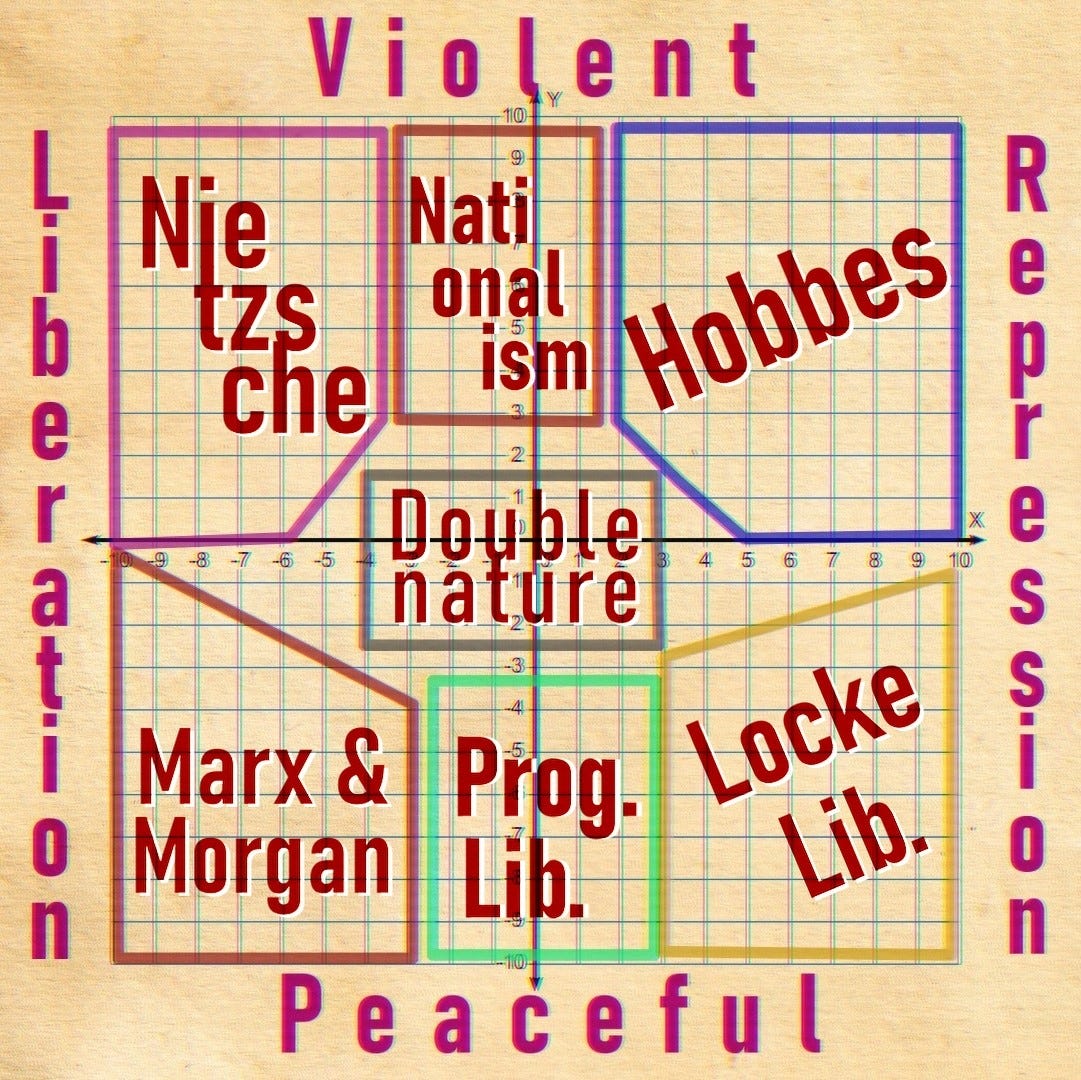

This map will be similar to the political compass, it will have two axis that will altogether create four different quadrants. However, the difference is that we will be using “Liberation vs Repression” in the X-axis and “Peaceful vs Violent” in the Y-axis. Let’s define what we mean by these terms:

Violent vs Peaceful

Are humans violent by nature or are we peaceful? This is one of the oldest questions of philosophy and there have been enough people that have had both opinions. I believe that this is because it’s difficult to reconcile the caring and sociable part of our nature that we might see with our family, friends or lovers with the absolute brutality that humans are capable of in contexts of crime and war.

All sides in this compass agree that there is violence in the world, and quite a lot of it. However, the disagreement comes from the source of this violence, is it intrinsic or is it learned?

The side that argues that human nature is peaceful believes that people are naturally good but that they are corrupted by society and, as a result, society is responsible for the cruel acts that people commit, not their nature. This means that in a perfect society, which does not exploit and corrupt, but instead, one that nurtures and gives, violence would simply cease to exist.

On the other side, you have the violent view of human nature which holds that humans evolved under harsh Darwinian conditions in which aggression was beneficial. Therefore, this view holds that our instincts are themselves ineradicably violent. They believe that society is able to tame these instincts, indeed, repress them completely, but never fundamentally change them.

As a rule of thumb, we can also say that the ideologies that hold human nature to be peaceful are also more egalitarian while those who believe that we are by nature violent also tend to think that humans are inherently unequal, because violence implies some state of inequal power with an aggressor and a victim.

Repression vs Liberation

On the Y-axis we have the second great question about human behaviour: Should one embrace one’s instincts, or should we resist and constrain them?

We can define repression as the effort used to steer the behaviour of the individual counter to their natural instincts. Of course, this is something tangible that we can observe; it is the pressure that an ideology puts on the individual through socialization, law and, perhaps most importantly, inner guilt.

This pressure can be used to steer man in many directions, the direction will depend on which instincts are being repressed. For example, if you repress our hedonistic tendencies, the result will be ascetic chastity, and if you do the same to the survival instinct you can achieve aerial seppuku. On the other hand, liberation is easy enough to define, it is the absence of this pressure in favour of the free expression (and often glorification) of instinct, whatever it might be.

The core disagreement between these two sides is on their opinion of human nature. The side of liberation believes in what they do because they have a high opinion of human nature, while the side of repression sees our instincts as dangerous and immoral. It is only logical that you will try to constrain human nature if you believe that it is inherently wicked, and that one should strongly oppose such measures if one believes that it is beautiful and good.

Now that we have defined these terms, we can begin to describe the different stances on our nature. We will try to present each one of these opinions of human nature in a persuasive way, because there is a reason that each one of them has managed to convince millions of people and inform dozens of ideologies.

So, let’s begin.

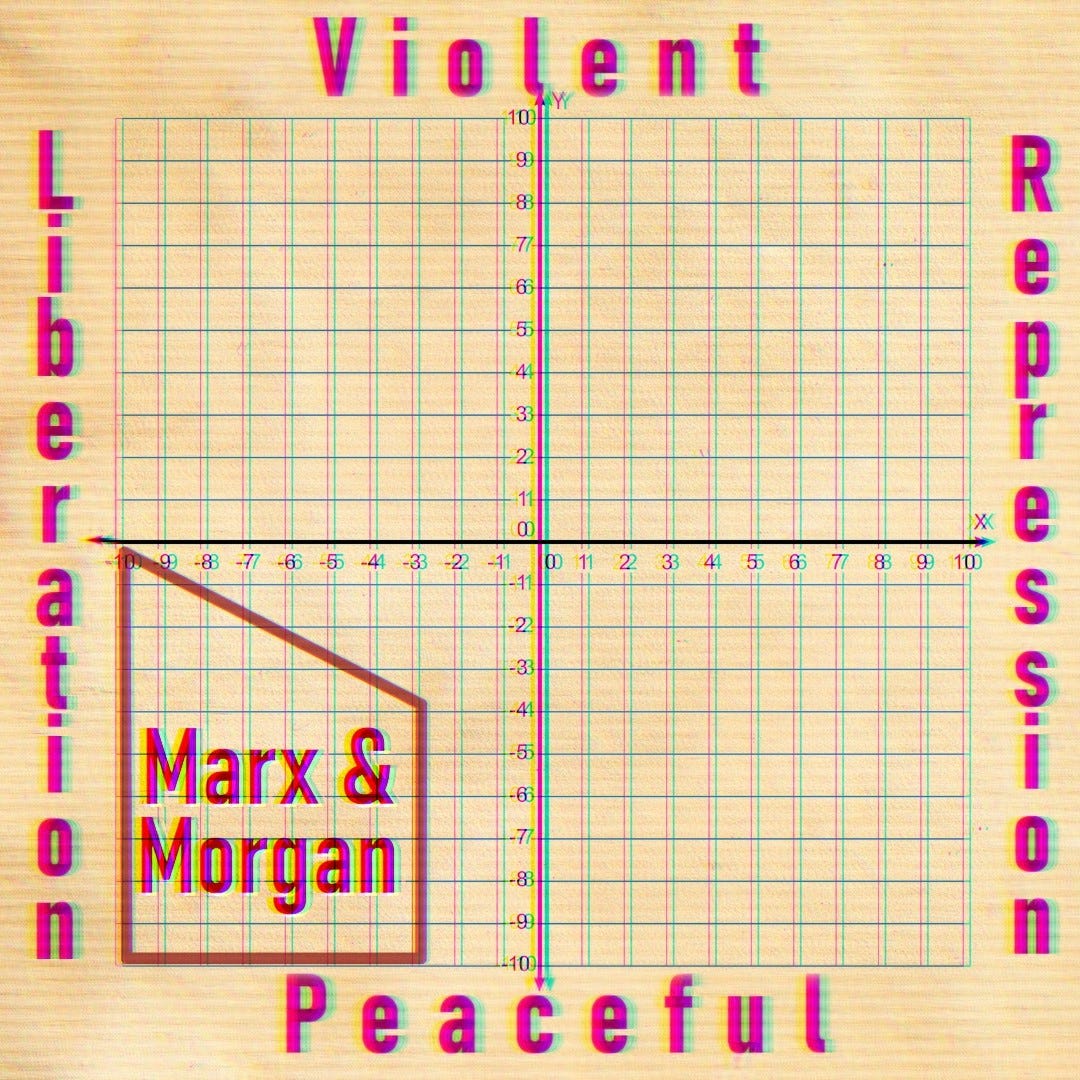

I. Primitive Communism (R.Walter)

How did social inequality come to exist? Some argue that it has always been present, that it represents an inevitable and natural state of affairs. Others, such as Marx and Engels, believe that social inequality represents a deviation from nature. They argue that man originally lived in small, tight knit communities, where everything was shared. The notion of private property did not exist in these communities, nor did significant inequalities.

In short, they argue that the natural state of man is communism.

To understand how they came to this conclusion, we must first examine the intellectual climate in which thinkers like Marx and Engels lived. In other words, we need to delve into the intellectual climate of the 19th century.

In the 19th century, historians began applying Darwin’s theory of evolution to the study of the past.

This evolutionary view of history imagined the past as a ladder. At the bottom, you had hunters and gatherers. On the next rung were pastoralists, who tended herds and flocks. Above them were farmers, who cultivated the land. At the top of the ladder stood industrial and commercial Europe.

In short, mankind developed in stages, and each stage was an advance on the previous stage. Just as man had evolved from apes, the industrial civilization of Europe had evolved from earlier societies that hunted and gathered.

One of the most prominent advocates of this view was the American anthropologist, Lewis Henry Morgan.

Morgan studied American Indians, and spent part of his life among the Iroqouis. In his early thirties, he published a book on their habits and customs. In this book, he claims that the Iroqouis lived in a state of primitive communism.

According to Morgan, Indian families would live in a joint-tenement building, called a longhouse. Several Indian families would live in this building. There was no concept of private property or land ownership among them. Property was the possession of the community, rather than the individual or family. To quote him:

“Whatever was gained by any member of the household on hunting or fishing expeditions, or was raised by cultivation, was made a common stock. Within the house they lived from common stores.”

The longhouse was supervised by a matron, who was responsible for distributing the provisions. To quote Morgan once again:

“Every household was organized under a matron who supervised its domestic economy. After the single daily meal was cooked… the matron was summoned, and it was her duty to divide the food, from the kettle, to the several families according to their respective needs.”

Morgan describes Indian society as a ‘gynocracy’, because it was matrilineal and matrilocal. In other words, descent was traced through the mother, and men lived with their wife’s family after marriage.

In 1877, Morgan published his most influential work, titled: Ancient Society. In this work, Morgan argues that primitive communism was not unique to the tribes of North America. Instead, he saw it as a stage of societal evolution that all people went through. He believed that gynocratic, primitive communism “had a wide prevalence in the tribes of mankind, Asiatic, European, African, American, and Australian. Not until after civilization had begun among the Greeks, (…) was the influence of this old order of society overthrown.”

In other words, primitive communism was the first stage of human development. It was, metaphorically speaking, the first rung on the ladder.

Morgan outlines seven stages of human development in his book. The first stage is primitive communism, as has already been said. The seventh stage is civilization. Societies in the early stages of development are polygamous, communist, and matriarchal, while later stages are monogamous, capitalist, and patriarchal. He thought that all societies would climb the seven rungs, though some were still resting on the lower rungs.

Most interestingly for our purposes, he predicts that one day, an eighth rung of the ladder would be climbed. This 8th stage would combine the benefits of present-day civilization while restoring the communal ownership that had existed in primitive societies.

This idea became an important part of the socialist view of human history. Both Marx and Engels read Morgan and adopted his ideas. Morgan’s ideas about primitive society also became dominant in the Soviet Union, and even Stalin incorporated them into his theories.

Morgan’s ideas about primitive society were appealing to communists because they suggested that communism was, in fact, natural. Rather than being at odds with human nature, as so many of its opponents claimed, communism represents a return to a more natural way of life—one that existed before the rise of private property and class structures.

Now that we have discussed what primitive communism is, and how the idea came to be, we are ready to place it on our map.

On the Violent & Peaceful axis, primitive communism clearly aligns with the peaceful side. Communists believe that violence can be attributed to private property. People don’t fight because they are inherently violent; they fight to secure resources. Therefore, when resources are shared equally among people, violence subsides.

On the liberation vs repression axis, communism leans heavily towards the side of liberation. Marx believed that the ideal society that comes after socialism is stateless and therefore without an oppressive structure. After the liberation from scarcity and class exploitation, each individual would have the freedom to authentically express themselves.

In the early stages of human development, when tools were simple, survival relied on cooperation within small groups. Humans were largely altruistic and egalitarian, because they had to be. But as society progressed, technological advancements allowed people to produce goods more independently. Consequently, they became more individualistic and competitive, prioritizing personal success and ownership over collective well-being.

In the Communist Manifesto of 1848, he marveled that the industrial revolution had “conjured up such gigantic means of production and exchange,” to the point that there were now more goods than could be sold. He believed that this technological advancement would lead to a new type of society and a new type of man. The 8th stage of the ladder would finally be climbed, and the end of history would be reached.

II. Hobbesian Conservatism

Hobbes is seen historically as one of the more pessimistic thinkers when it comes to human nature. His view is that human nature is savage and that life in our “state of nature” was, in his own words, nasty, brutish, and short.

To understand this idea we must first look at the life of Thomas Hobbes and what led him to think this way. Hobbes was born premature in 1588, allegedly because the invasion of the Spanish armada scared his mother so much that she gave birth before the pregnancy was complete. He was later quoted as saying that his mother gave birth to twins; himself and fear.

In his adult life he also experienced the English civil war and the period of anarchy and almost constant conflict that followed the series of bloody wars between the parliamentarians, the royalists, the Irish, and the Scots.

This led him to conclude that the breakdown of order, of state authority, led to suffering on a grand scale. In his most famous work “Leviathan”, Hobbes advocates for an all-powerful monarch to bring an end to anarchy. But one that was not king because God appointed him, instead, he stated that a king’s right to rule came from his obligation to protect the people from external threats, but even more so from themselves when social order broke down. This was the first instance of the idea of the social contract.

We should take into account that the English civil war was a very mild war by historical standards (except for Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland). When reading about the more brutal wars and crimes in history one really cannot help but come to understand Hobbes’ way of thinking.

There are no lack of examples of brutal wars and massacres, but let’s look at one of them, chosen for no particular reason: The sack of Aquileia by the Huns in 452. Not much is known about the siege other than the Huns broke into the city and then proceeded to brutally sack it. We do not know how many were killed, raped, and enslaved, but we can certainly say that thousands were butchered.

We do not really need statistics to imagine the scene; a dozen Huns breaking into a house, killing the parents, raping the daughters, enslaving the survivors, and finally torching the home of a once happy family. Imagine the terrible suffering of this one scene alone and now multiply it by ten thousand just for this one minor siege. If this does not convince you of the human capacity for violence, then multiply the unimaginable suffering of the siege of Aquilea by at least another 10,000 to account for all the sieges and sacks in history where a civilian population was massacred.

Just from multiplication we can imagine 100,000,000 families being brutalized in the last 3000 years. Perhaps this is even a low estimate given the scale of the World Wars (90 million deaths), the Mongol invasions (40 million deaths), the Chinese changes of dynasties (20-ish million apiece) and so on. One can barely even comprehend the suffering experienced during a single murder, mutilation, or rape, therefore, millions of them are simply unimaginable.1

But perhaps the most interesting thing is to ask; why did this happen? Did the Huns have any reason to massacre this city in such a brutal manner?

Well not really, the Huns after all were steppe nomads, there was nothing in Aquileia that they needed, their pastoralist lifestyle really only needs grass and cattle. So, what was the point of invading and sacking a far-off city?

Well, their nomadic lifestyle led them to be great archers and warriors, this gave the Huns a lot of power. They could go anywhere, defeat the local armies and do whatever they wanted. So, they did, they decided to ride halfway across the world to rape and murder. To be more concise; the Huns put thousands of families to the sword because… because they could.

However, this is in principle no different to how most crime happens, most criminals do not steal, rape, and murder because they are LARPing Robin Hood or because they will otherwise starve, but instead, they do so because they are armed, and their victims are not. In other words, because they can.

As already mentioned, at the core of Hobbes’ philosophy was fear, fear of what humans are capable of when given the chance. Perhaps this way of thinking will not resonate with many, but this is because most people in the west do not know fear; they live in societies with (relatively) low crime and have never experienced war.

But those who have felt this fear in their own lives know the brutality that humans are capable of and therefore they also know the value of security and an orderly society. This is exactly what makes Hobbesian Conservatism attractive in times of trouble.

This view of human nature informs the part of the right wing which is primarily concerned with law and order. It promises to tame the bestial nature of unleashed man. Indeed, his faction becomes stronger when there is more crime, war, and chaos in a society, and it becomes weaker when society is orderly, peaceful, and safe.

So, it is somewhat ironic that its success in creating safety eventually leads to conservatism’s own downfall. Perhaps the most famous example is the election of Guliani as the mayor of New York on the promise to clean up the city, after significantly reducing the crime rate, New York stopped voting for conservative (Hobbesian) candidates and the machine successfully unplugged itself.

III. Optimistic Liberalism

On the intersection of repression and the belief that humans are by nature peaceful we find Optimistic “everything is fine” Liberalism, which is certainly the dominant opinion on human nature in the first world.

This quadrant believes that the great majority of people are normal. “Normal” in the sense that they are not violent or cruel, and that these regular people are interested in living an average life where they own a House with a garden for their golden retriever, as well as a car or two, and even can afford a trip to a Cancún resort once year.

I believe that this view of human nature is so popular because of the conception that most people have of themselves; there are very few people who see themselves as bad, cruel, and violent. Even many violent criminals believe they are fundamentally good people in unfortunate circumstances.2

As a result of their belief in their own goodness, most people assume that this is applicable to everybody else. It is easy to see why this is so popular in orderly countries with low crime rates and relative prosperity. In such societies the average individual is more interested in paying off their mortgage and going out with friends next Friday, instead of robbing and stabbing his fellow citizens.

The liberal rejection of the Hobbesian concept of human nature is, in this sense, quite logical since their experiences with other people are either mundane or generally positive. Most people in the first world have never seen or could imagine the violent state of existence that Hobbes describes.

Indeed, liberalism states that those who are malicious are only so because of bad environmental factors such as poverty, trauma or mental sickness; a liberal cannot imagine a rational actor choosing to commit violence.

The ideological roots, of course, come from John Locke, the first Lib. His ideas about human nature come mostly from his work "Two Treatises of Government". Here he states that humans in the state of nature possess absolute freedom over themselves which is granted to them by God.

Locke believes that in the state of nature all men are equal in their God-given rights to life, liberty, and property and that if any man were to infringe on the rights of another, this would represent a violation of man’s rights; indeed, a violation of natural law.

I think it is pretty safe to conclude that Locke thought that human nature was fundamentally good since it is the creation of God himself, after all, John Locke was a lifelong Protestant. However, we must also take into account that this view of human nature does not embrace liberation in the hippie sense, classical liberalism still follows a religious morality that required the repression of certain instincts to be a proper God-fearing Christian. Indeed, later John Adams stated that:

“Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious People.”

I think it is important to draw a distinction between Locke's liberalism (which is most often called “classical Liberalism”) and Progressive liberalism (the type that is taught in university and can be found in the New York Times) which is strictly secular. It relies on the Declaration of Human Rights, instead of God, as an ultimate moral authority and is most often this is justified though utilitarianism; if human rights are violated, people suffer and therefore human rights are good.

Although progressive liberalism might seem closer to liberation, repression is still present, not because they believe that human nature is inherently violent, but because of the fear that if socialization is not properly carried out, this could lead to illiberal attitudes and thus to violence. This does lead to a different sort of repression that is typical of modern education. It represses all behaviours that are seen as potentially dangerous and steers developing minds away from reactionary ideas.

This principle can also apply to Morgan, Marx and other revolutionary thinkers when they encounter violence that does not evaporate when society is reformed to abolish oppression. If one believes that violence is socially learned, then the presence of violence must mean that there is some element of social contamination that must be stamped out, and so, one can have repression even while one believes in liberation.

There is also an important gendered component to this, males are far more propense to violence. If you believe that human nature is peaceful by nature, this means that men are more easily corrupted into violence than women. Thus, men in a progressive liberal society face much heavier repression than women. (And it is no surprise that most men find themselves on the other side of the map.)

Fundamentally these two approaches to liberalism, both religious and secular, agree that human nature is fundamentally good, but that there are still certain principles that must be followed, and which will require some repression. Although it must be said that the manner of repression is less direct than in Hobbesian conservatism.

The belief in the goodness of people will thrive under conditions of material prosperity and security. When these conditions are not present, modern optimistic liberals are forced to contrast their view of human nature with the violence that humans are capable of, and this is no easy task. An increase of violence and hardship in society normally results in a shift towards Hobbesian conservatism.

We have already mentioned the inverse pipeline where Hobbesian Conservatives become optimistic liberals when they let go of the fear that characterizes them. These two quadrants have an ironic cyclical relationship where the success of one of them leads to its ideals being abandoned in favour of the other’s.

But it must be said that there is wisdom in the core idea that most people want to live a normal and happy life without harming others in any way and as a result, liberalism’s description of human nature is mostly correct inside of places like Denmark, however, this view collapses in the rest of the world.

IV. The New Barbarians

The difference between the new barbarians and the other quadrants is that they essentially glorify and come to accept violence as an integral part of human nature. The peaceful side of this map obviously rejects all forms of violence as unnatural and profoundly evil, while the Hobbesians believe that man’s violent nature should be repressed and domesticated.

The people in this quadrant agree with the Hobbesians that human nature is brutal, as well as unequal, however, they embrace it and choose to let human nature loose instead of trying to tame it. This position clashes directly with the morality embraced by the other 3 quadrants which repudiate violence, however, what is the rationale that this quadrant uses to justify its glorification and embrace of violence?

We can divide this section into two different groups, the first group are the Nationalists who also represent a large part of the world’s population, perhaps the largest competing only with the optimistic liberals. In this category we can put the people who are explicitly patriotic and that believe that their nation is special in some way or another. However, the connection between having an ethnocentric worldview and believing that humans are inherently violent is not obvious.

Every ethnic group defines itself in relation to other groups that are different to them; to be Estonian can only make sense in a world where there are other people who are not Estonian. This means that all groups, from high-school cliques to 1000-year-old cultures, must draw a border between themselves and the rest of the world to give themselves an identity; to define who is one of us and who is one of them.

It follows that different groups will have conflicting interests especially taking into account that societies grow and constantly need more land and resources. This almost always leads to competition between societies and these conflicts are often, with only a couple of exceptions, resolved by some type of violence.

Therefore, modern nationalists believe that the world can be best understood as a hostile place where different nations and peoples struggle against nature and each other for survival. Essentially, their view of human nature comes down to the idea of Darwinian selection among competing groups.

There is more than enough historical evidence to vindicate the idea that history is driven by civilizational conflict, also known as war. Indeed, you would be hard-pressed to name a single nation that was not established as a result of one civilization vanquishing or assimilating another.

English, the language of this essay, is an Indo-European language, this language family originated from the Caucasus over 5000 years ago. The ancestors of the English came down from the steppe and conquered the Early European Farmers (EEFs). This is the reason that Indo-European languages are spoken from northern India to Ireland. In the specific case of Britain, this conquest replaced approximately 90% of the EEF gene pool in the period of a few hundred years (i.e. quite a brutal conquest).

Indeed, historically one can observe that the cultures that are more militaristic and glorify violence tend to become more powerful and dominant; for example, it is no surprise that it was Prussia, and not the Hansestädte, that unified Germany.

This means that violence between different peoples with conflicting interests is just a fact of life and a necessary part of group survival. Therefore, this quadrant does not shy away from violence because it sees it as something practical; it observes violence in Darwinian terms. This analysis might be cold and amoral, but at least it can point to historical precedent to justify itself.

The second group is much newer, but no less interesting, they are best described as the Aristocrats. They have many similarities with the nationalists; they also have a similar belief structure, but they take the idea of Darwinian struggle further. The nationalists believe in inequality among nations, but equality within the nation.

However, the aristocrats reject this concept of equality in their own society and introduce the idea that the superior members of society (themselves) have the right to lead and lord over the plebs. Classical aristocracy, the type that used to dance around with whigs, doesn’t exist anymore, so, this section is dominated by more modern concepts of aristocracy.

Certainly, the most influential modern proponent of aristocracy is Friedrich Nietzsche. According to him, man is driven by the pursuit of power, power over matter, and most importantly, the beings around him.

"What is good? All that heightens the feeling of power, the will to power, power itself in man. What is bad? All that proceeds from weakness."

The Antichrist, Section 2

This means that there is a constant state of conflict among nations, classes, and finally, individuals. All conflicts end in victory and defeat and in a war of all against all, the strong triumph over the weak and come to dominate and exploit them.

To Nietzsche, all of this violence was justified in the name of higher culture, in the name of art, indeed, Nietzsche believes that art itself is what redeems humanity. He argues that only aristocracy can produce high culture, and to have an aristocracy with enough strength and time in their hands to create art, one needs to exploit the labour of the plebians who cannot produce said culture. Perhaps the society that best embraces this is ancient Greece, the Greece of Homer; a warrior culture of powerful and prideful men who reached the heights of art.

From the aristocratic point of view, human nature is violent and seeks power over his fellow man, furthermore, this is good and is a healthy expression of life, that the moral condemnation of violence is contrary to nature itself:

"To demand of strength that it should not express itself as strength, that it should not be a will to overpower, a will to rule, a will to become master, a thirst for enemies and resistance and triumph, is just as absurd as to demand of weakness that it should express itself as strength."

Beyond Good and Evil, Section 13

The nationalist view of human nature does require some median level of repression in order to have an orderly and unified society, on the other hand, the aristocratic view, is against all repression and favours the liberation of all nature, of all instinct. Indeed, in terms of violence, nationalist violence is colder (more Apollonian) than the passionate (Dionysian) violence of the aristocrats.

I decided to call this quadrant “the New Barbarians” because both the nationalists and the aristocrats have rejected both the Christian and humanist values of universal empathy and of human rights like many of the civilizations of past ages such as the Romans and the Scythians.

The result is a view of human nature that embraces both Darwinian violence and breakneck scientific progress, a dangerous combination, to say the least.

Review

There are also many people who are moderates in the question of human nature, they find themselves in the middle of the map and believe that human nature has many facets. That there is a part of human nature that is violent and another that is peaceful and that this means that one needs a mild amount of repression to be able to control these aspects of human nature. However, they have to justify their own position of there being multiple, separate facets to human nature.

Therefore, the final map of human nature would look something like this:

My own position on the map is about halfway towards the violent side and about center in matters of repression. In my opinion, it is undoubtable that we are violent by nature and that this is clear from the study of history to the way that 4-year-olds play with their toys.

The reason that I find the “violence is learned” explanation to be unsatisfactory is that there are very few examples of peaceful societies, a handful of geographically isolated tribes such as the Moriori, but for every such tribe there are 10 Prussias. Beyond that, one can observe organized violence in chimpanzees in the Gombe chimpanzee war. Are we supposed to believe that these chimps were born peaceful and were corrupted into ambushing members of the other tribe and beating them to death?

(Indeed, exactly this was the accusation that was thrown at Jane Goodall, the reasercher that observed this war. Her critics defended the past consensus that chimpanzees were naturally peaceful by arguing that the cause of the violent behaviour was Jane herself, who gave the chimps bananas.)

On the side of repression and liberation I am, strangely, a centrist. Pure repression is, first of all, ugly to look at. But an actual argument is that excessive repression makes both society and individual weaker. It takes a lot of energy and suffering to completely repress an instinct, so, it in not something to take lightly.

I would say that the repression of certain instincts (Delayed gratification, avarice, envy, general sadism, etc.) is necessary for there to be civilization at all. But denying oneself, as if you were an Ascetic monk is not recommended, this requires huge amounts of energy that most people cannot even muster and even when it is successful, it just generates a lot of neurosis (E.g. girls who went to catholic school) and excessive rigidity at both an individual and a social level.

This, in the long run, makes for backwards and brittle societies, some examples are the ultra-isolationist Tokugawa Shogunate which was completely unprepared to face the world when it showed up to their door and the traditional lifestyle of the amish, who can only live in the shadow of an empire, given that they cannot defend themselves.

How to use this map

Your own politics will depend on your conception of human nature, I think that is clear. However, one cannot know everything about an ideology or a political movement by knowing their opinion of human nature. It can be a reference point, but real political interests and culture still have a significant effect on the way that an ideology or movement develops.

But often political discourse is doomed to break down because both sides have conflicting ideas of human nature and therefore it might as well be that they are speaking separate languages or talking about different species. All of these interpretations of human nature are based on individual experience and each one roffers a deep and convincing image of what it means to be human.

Without this frame of reference, without knowing how the people on the other side of the political spectrum think about themselves, I’m afraid that no understanding and no dialogue will be possible.

I hope that this essay and this handy map might facilitate this.

Perhaps the only people who are convinced that they are bad concentrate in depressive patients, hardly the most vicious section of society. On the other hand, many criminals look at their actions in a passive way in order not to come to the conclusion that they are violent and guilty, this is the theme of the 4th chapter of Dalrymple’s book "Life at the bottom”.

Yeah, I think if I am level headed, I would put the truth at the exact center. That being said, since our society is dominated by progressives and marxists, I pretty much sympathize with everyone else: the nietzschiens, nationalists, hobbesians, and even Lockeans to a lesser extent. I tend to view ideologies that view human nature as good as false and suspicious due to my theology; however humans do have a capacity for good. Center is healthy, but it looks like Hobbesian nationalism because of the current state of the West.

Fascinating 🤨 human societies are so diverse and complex. Thanks